Solvitur ambulando, attributed to Diogenes (@400 BC), St Augustine (@400 AD) and advocated by Nietzsche who (depending on the translation) wrote ‘All truly great thoughts are conceived while walking‘ or ‘Only thoughts reached by walking have value’. When Chrissi Nerantzi invited representations of Wondering While Walking I straight away thought of labyrinths. My Walking the Labyrinth blog had followed the concept as a tool for learning development, in particular reflection and stress relief before exams. Walkers reported feeling calmer after their labyrinth experience. It’s hard to explain unless you’ve tried it. Although the process will always be individual, the best way to describe it is probably as ‘time out’; something it can be hard to make time for!

There are few rules to labyrinth walking but it helps to be silent and focus attention outwards on the twisting path into the centre and out again, while keeping the inner attention quiet. Concentrate on each step, like a walking meditation or practising mindfulness.

You can create a labyrinth yourself, on the beach, on grass, on paper, then walk it or trace it with your finger. Original turf labyrinths exist in England, some of which are maintained and can still be walked. Julian’s Bower at Akeborough in North Lincolnshire and Walls of Troy near Dalby in North Yorkshire are the two nearest to Hull.

Labyrinths can also be explored in books or online. Around the turn of the 21st century there was a revival in interest and there are now a number of labyrinth societies supported with research and publications. Although there are many different theories around their origin and use, the truth remains veiled in mystery.

In 2014 I was invited to write the texts for the University of Lincoln Labyrinth Festival. A large 13 ring medieval Chartres style labyrinth was chalked onto the nave of the cathedral and visitors invited to walk. Exhibition panels were mounted within the arches down the side. Each panel contained a labyrinth image and my words which aimed to provide a synthesis of what is known. An edited version is below.

Introduction

To walk a labyrinth can be a form of meditation, offering stillness in a busy world. The experience can be whatever you want; contemplative, healing, mindful, prayerful or simply fun. The origin of the labyrinth is unknown. Today is it a ritual where past and present come together. Labyrinths are for everyone. All you need to walk a labyrinth is yourself.

Seven things we know about labyrinths

1. we know labyrinths are mysterious

The absence of knowledge around the origin and purpose of the labyrinth encourages individual meanings. Walking a labyrinth can symbolise an act of celebration, prayer, reflection, remembrance, solace or simply time out of a busy day. Some believe they are merely patterns while others say they represent the archetypal journey from birth to death; the twisting and turning path indicative of life’s challenges. The interpretations attached to labyrinths are adjustable. They can be as shallow or as deep as anyone wants or needs them to be.

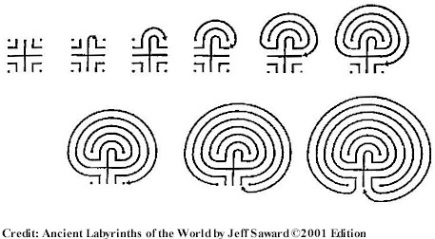

2. we know labyrinths have an ancient past

Circles carved onto rocks and spirals scratched on stone could be precursors of the labyrinth design. The three and seven ring ‘classical’ labyrinths pre-date more complex 12-circuit medieval designs. Even the origin of the word labyrinth is obscure. Some say it derives from Labrys, a double headed axe from Minoa, or the Greek laburinthos but no one knows for sure. Both function and meaning of the labyrinth are lost in time, which is part of their mystery and attraction.

3. we know labyrinths appear in history and religion

Lucca’s Duomo di San Martino in Tuscany contains a 12th century finger labyrinth on the wall by the entrance with the Latin inscription This is the labyrinth built by Daedalus of Crete; all who entered therein were lost, save Theseus, thanks to Ariadne’s thread. The story of Theseus tells how the prince entered a labyrinth to slay the Cretan Minotaur, a monster who devoured humans. Deadelus, the master architect of the labyrinth, is said to have also built a special labyrinthine floor for the princess Ariadne to dance on. Labyrinths have been found on mosaics in roman villas, on coins, manuscripts, churches. There is one in the 13th century Chartres Cathedral in northern France. Church records show others were built at this time but later destroyed. References to Easter processions by priests, and a distant law preventing congregations from dancing, suggest an association with rites long forgotten. Today the past and present come together in Lincoln Cathedral and visitors invited to take time out to experience the labyrinth for themselves.

4. we know labyrinths are not mazes

There is widespread confusion between mazes and labyrinths. Mazes are designed to disconcert and deceive; to be puzzles and sometimes places of frustration and fear. A labyrinth is different. It has a single unicursal path.Yet dictionary and encyclopedia definitions repeatedly describe labyrinths as mazes. This is incorrect. You can’t get lost in a labyrinth. It has one single, winding path into the centre and out again. The only choice needed is to walk over the threshold and take the first step.

5. we know labyrinths imitate nature

Circles and spirals can be found in the natural world. The curve of an ammonite, the winding tendrils of climbing beans, the twist of hazel and the delicate fronds of bracken as they open to the light. A labyrinth path mimics the mathematics of circles and circumferences, of beautiful and sacred geometry. Our lack of knowledge about their origin only reaffirms what is not known sometimes doesn’t matter. We don’t need definitive answers to experience the labyrinth journey. It is for all seasons and all people.

6. we know labyrinths can be made from stone, sand, chalk, grass

Turf labyrinths have been cut from the earth beneath our feet. There is uncertainty about their exact age or purpose. There are a number of public turf labyrinths in the UK, all well maintained with edges cut and grass trimmed each year. You can find them at Akeborough, North Lincolnshire; Dalby, North Yorkshire; Wing, Rutland; Hilton, Cambridgeshire and Saffron Walden in Essex. Their fresh grass paths carry the imprints of generations of children and adults. They link centuries of people through a shared experience of walking, running, dancing into the centre and out again.

7. we know labyrinths are enduring symbols

A resurgence of interest has resulted in labyrinths being used for workshops and conferences in health care, education, counselling, spirituality, retreats. Portable labyrinths have been painted onto canvas. Temporary ones constructed on beaches or made with sticks and stones in parks and woodlands. They can be made of leaves, bird seed, masking tape, grass paint. Wherever there is space and time a labyrinth can be constructed. Always leave them for others to find before the tide comes in, before the wind blows or the rain washes them away. Draw your own labyrinth on paper or card. Stitch or knit one. Explore the meandering, wandering path with your finger. The circuits are rhythmic and soothing. This will never change. Labyrinths have endured for millennia and will continue to do so. They are sources of creativity for us all.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

Twilight of the Idols (various translations) Friedrich Nietzsche (1888)

Visit Wondering While Walking to contribute to the #www16 project