The family refer to Alexa as ‘she’.

Alexa is artificial intelligence, built to respond to commands and presented as female. Unlike a sat nav, you can’t change the gender. While some say the voice is androgynous, to me it sounds like a woman and this is uncomfortable. It worries me.

What also bothers me is the way I see people talk to Alexa. The ability to demand an action, the lack of please and thank you, is rude. It must be having an effect, in particular on young minds who are are also having the socio-cultural associations between women and service being reinforced.

The family laugh at my concerns but the habit grows incredibly fast. By the end of an hour I’m saying ‘Alexa, volume 4’ to turn down the music which she (see what I mean?) was told to find. It’s alarming how quickly new behaviours are embedded. You get in the car, and ask for the radio. This is how fast ways of being change.

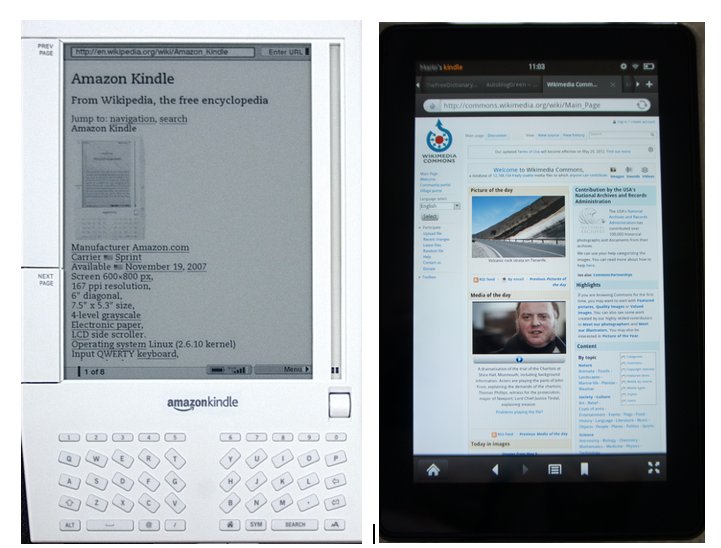

Alexa is early technology. This time next year it will have moved on, like the e-reader shifted from clunky keyboard to swipe screen. But where will Alexa move to?

I’m beginning to feel I’m on the wrong side of the digital revolution.

Words like revolution and transformation should be used with care. Easy to throw into conversations, their significance gets diluted by repetition, but when it comes to the social impact of the internet, language like this is appropriate. However, the implications of digital development are not yet fully understood – or feared.

Sometimes it feels like we’re walking into dystopian futures with eyes wide open, but not seeing. Alexa is the beginning but do we really need apps linked to fridges to tell us when to buy milk, have remote control of household appliances or be so totally dependent on electronic systems for storing and accessing our hard-earned cash. Is it wise to have the administration of our lives resting on cables running under the ocean, in particular for accessing public services, health and welfare. Is it? Really?

I’ve long had concerns about the consequences of unequal access but even as I write these words, I’m aware they involve unspoken assumptions the digitisation of society is good. It has advantages to be sure. But what is it doing to relationships and the quality of interpersonal communication? How is it changing what it means to be human?

I watch family interact with voice activation and the ways they use Siri on their devices. Actions which remove politeness and grace and replace them with commands. The technology we’re increasingly dependent on for the administration of day-to-day to life emerged from controlling weapons of war, the language of computers still reflect their military origins and remnants of this remain.

Failure to initialise. System error. Fatal exception. Corrupted file. This week I saw the message ‘You have aborted this video’. Then there’s the dreaded ‘Word is not responding’ followed by ‘Word is shutting down’ when you’re in the middle of a long document you haven’t saved for a few pages and Autorecovery is never as up to date as you need it to be!

We have less control over our devices than we think

If the machine was using us in 2007, think how much more it’s using us now!

Virtual reality is an artificial simulation but one at risk of being perceived as real. We think we know the difference but do we?

Spend an hour being disconnected. Extend the absence to a day or a week. How does it feel? I access my life through my laptop and struggle without it. This scares me but I can’t stop. Everything is online.

My Alexa weekend has got me thinking. Maybe we need to apply social theory to the digital domain. Revisit the social construction of technology. Theorise digital practice.

I drove to Manchester and where the M62 crosses the Pennines, the motorway becomes vulnerable to the weather. Its high up and exposed to cross winds. Snow quickly settles in the outside lane, where poor driving conditions increase risk of accidents as visibility worsens and the road surface is icy. Good drivers adjust their speed while others power on, feeling secure in their metal bubbles.

Motorway driving is dependent on individuals following the rules of the highway code. Keeping a safe stopping distance from the vehicles in front. Showing courtesy to other road users. A busy motorway is like an artery. So long as there’s no obstructions people should reach their destinations safely. But as we’re continuously told, hearts need to be kept healthy, with attention to diet and exercise supporting the free flow of oxygenated blood around the body.

Social life is not so different. It requires compassion. Care. Kindness. Understanding how little things matter, like when you’re driving and a stranger smiles as you stop at a pedestrian crossing, or a quick flash of the lights when someone les you out at a difficult junction, a hand raised in acknowledgement to say thank you.

Technology has long been a primary driver of social change. This can be good. Digital developments, where science, engineering and the arts come together, have the capacity to alter the world, make it a better place, one which supports individual health and happiness. So long as the ways in which the affordances aim to improve the human condition, not diminish it.

You can re-programme Alexa’s ‘wake-up’ but the default setting is a command.

‘Alexa’

Would it have been so hard to make ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ a requirement of use? The ways in which technology usage can influence attitudes and actions are known yet it’s deemed ok to demand a service rather than request it.

People will talk to their device as they talk to others, and ‘Alexa’ can be said as a question as much as a command, but the lines are thin and blurred. Usage will be diverse and it seems a missed opportunity to build some kindness into what feels like an increasingly hostile world.

It bothers me that criticality appears to be waning and there’s an absence of digital mindfulness.

‘Alexa, what should we do?’

‘I’m sorry, I don’t understand the question.’

Since writing this, Amszon have announced Amazon will start letting random people provide Alexa answers. A topic for a follow-up post but here some points for critical relfection from the article.

“The system will use game mechanics to engage users — people will be able to earn “points” each time the assistant shares one of their answers. But as other platforms…have discovered, user-generated content is open to mischief and propaganda. It’s easy to imagine the kinds of answers somebody might submit for questions about Donald Trump or measles vaccines, for instance. Amazon [says] it’s relying on a combination of algorithms and human editors to help vet responses and hoping that a system of user up and down votes will weed out mischief-makers. But previous experiments with user-generated answers, such as Yahoo Answers and Quora, have never really taken off, so Amazon has a hard task ahead.”

Why is Amazon doing this?

Kindle images from

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/14/Amazon_Kindle_-_Wikipedia.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kindle_Fire_web_browser_05_2012_1430.JPG