As I prepare to leave my current role, my visible digital participation has reduced to an occasional retweet. I’m now watching from the sidelines, observing and thinking about future directions.

I’ve become a lurker.

The Other Side of Lurking: Part Three follows others* on the Digital Academic blog, all addressing the issue from a range of different perspectives. You might think there isn’t much more to say, but if lurking practice is more common than active engagement, there’s a need to focus on what digital silence means for the future of online education.

The OER19 conference at Galway included a workshop titled Three Lenses on Lurking. It was facilitated by my online colleagues Leo Haverman, and Caroline Kuhn. Along with Aras Bozkurt, we’ve been discussing lurking for some time. Participating in this investigation into lurking behaviors was valuable experience but over the past few months I’ve become the lurker in the group. Distracted by an institutional review and the final stages of my PhD, my active participation faded. Lurking made it possible to continue to follow discussions and reflect on ways forward, but it excluded my voice.

Yet, we know lurking is common practice. Applied to online participation, Neilsen’s 90-9-1 rule (2006) and the 80/20 Pareto Principle (1971), quoted in Sarah Honeychurch et. al.. (2018), reminds us how more people adopt lurkish stances than proactive ones. Other papers such as Preece and Shneiderman (2009) reinforce how reading dominated leading, with passive access more frequent than interaction. These authors cite Kollock (1999) who calls lurking an activity which does not produce a visible contribution. Like watching and listening.

Can these practices still be as influential as active participation, here and now in 2019?

From decades of experience supporting online education, alongside all my research into digital practice, I would say No. Yet many can give examples where passive engagement has been valuable. My education developer head underpins effective pedagogic practice with social constructivist theory, but the reality suggests there’s times and places where access-only appears to be enough. If digital shyness is more common than digital participation, then clearly it should not be ignored. Rather than perceive it as resistance, we need to work with it instead.

I’d suggest lurking matters because it highlights the under-addressed gap between theory and practice in online education. For the past two decades, learning and teaching has been filled with the promise of technological transformation. However, all too often the digital experience remains a case of ‘I set up a discussion forum but no one used it, so I didn’t bother again‘.

For many years I’ve believed finding ways to encourage and support online interaction lies at the heart of effective teaching and learning. But it seems regardless of what you do to encourage online activity, digital practice remains a personal choice and lurking the majority response. Maybe instead of trying to change this, we should find ways to reconceptualise it as having value.

I lurk. You lurk. We all lurk. Lurking has intention and purpose. If lurkish behaviors are to be understood as legitimate choices, do we need to review the construction of online resources and rethink pedagogic practice to support less visible activity?

This would involve exploring the causes of silence and accepting not everyone learns best through active engagement. Contribution should not be mandatory for those who feel less comfortable with online collaboration. Lurking might result in digital absence but as digital developers and facilitators of online learning, maybe we have a responsibility to listen and understand the ways this silence can contain its own messages.

If we need to design for legitimate lurking, what would this look like?

It seems a problem with advocating lurking as legitimate learning is how the approach challenges digital education theory. We’ve been told education is social and been offered communities of practice and inquiry, zones of proximal development, conversational frameworks, social, cognitive and teaching presences, all requiring interaction, the binary opposite to inactivity.

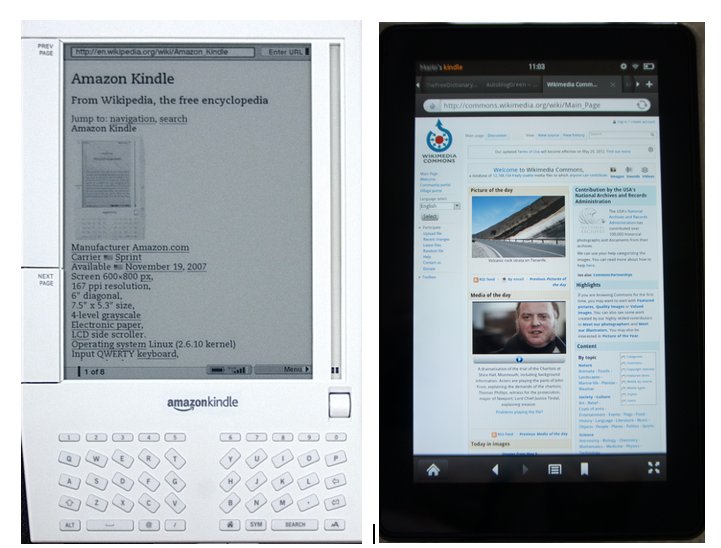

21st century digital practice has called for cognitive shifts. Promoters of online learning have advocated adopting models such as Salmon’s Five Stage approach to moderation and the establishment of e-tivities, Laurillard’s Conversational Framework or Garrison and Anderson’s Community of Inquiry. All based on the theory of social constructivism but as frequently happens where change is involved, these processes are situated within liminal spaces, where new approaches and knowledge can be perceived as troubling.

My doctoral research suggests digital practice is diverse and troublesome. Participants teaching and supporting learning, in particular the later adopters of learning technologies, need to make fundamental conceptual changes alongside the acquisition of digital capabilities and confidence. These involve shifts from didactic transmission to student centred co-construction of knowledge, approaches which contradict the suggestion lurking as valid learning.

However, without opportunities to watch, listen and read, those who are nervous and hesitant about online interaction are less likely to engage. The divides between the digitally confident and the digitally shy are wide and deep. My research findings suggest digital practice is more troublesome than the digital advocates might realise. The use of the internet challenges existing ways of working. It attacks academic identity and beliefs about knowledge in the way open education challenges the conception of publishers as gatekeepers. Individual response to these approaches cannot be assumed to be positive.

Digital practice is like other forms of physical skill such as riding a bicycle. It needs practice. But if you’ve been doing it for years its difficult to remember how it feels to be a novice. It’s the same with virtual environments. If you’re comfortable with online navigation and interaction it’s easy to forget what it feels like to lack digital confidence and be nervous about venturing into online spaces.

Advocating lurking as valid learning can feel like a backwards step. Everything I’ve done since entering higher education at the turn of the century has been focused on promoting and supporting online interaction. The literature speaks of developing relationships with students and building curriculum designs around collaborative approaches. We believe higher education is about more than acquisition. Using Laurillard’s six types of learning experiences, adopted by UCL in their ABC Currciulum Design work, it involves collaboration, discussion, investigation, practice and production.

How can this be achieved online where lurking is the preferred behavior?

If you can take a horse to water but not make it drink, maybe we need to begin looking at the water rather than the horse.

* previous blog posts addressing lurking

- Lurking as valid learning (March 2016).

- Reinventing lurking as working December 2016

- Sounds of Silence (April, 2018)

- The Other Side of Lurking Part One; a unique distance from isolation (July 2018)

- The Other Side of Lurking Part Two, searching for explanations, digital imposter syndrome or digital self-efficacy? (July 2018)