It’s so ironic…

I left work last September. My career in education was always centred around virtual learning so here’s the irony. At a time when HE has been forced into making a wholesale digital shift, I’m not there. Everything I worked on, presented, published and researched, was about teaching and learning online. I know how it works. The risks and benefits. Challenges and advantages. I’m comfortable setting up, moderating and participating in online study. I know my way around social media.

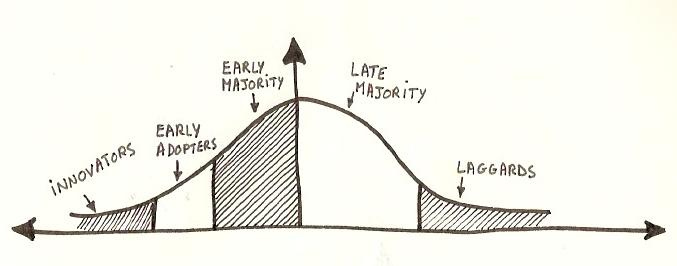

I have analogue roots and I know where we came from to get where we are today. For a long time, I was the digital academic with a passion for inclusion, in the final stages of a PhD. This was an extension of my work, documented across my blogs, and based on studying the digital shifts of staff teaching and supporting learning. Looking back, maybe it was too close to home. Maybe I was too much on the inside. I think I forgot how much an internet society champions progress rather than the baby steps needed to build initial access and interaction. My bad!

When the environment you were obsessive about is no longer there, it can make you reassess why you wanted it in the first place. This is what happened with the PhD. Once I moved from HE, I found the motivation and enthusiasm were draining away.

After the viva I went travelling. Greece, Turkey and Israel were all amazing and although the future is uncertain, I still have flights booked to Spain to walk the Camino Frances during October, then a trip to Jordan to visit Petra.

No longer being at work presented opportunities to re-engage with everything and everyone I’d neglected while my head was full of research and development. It became increasingly difficult to find PhD space in my head – or my heart.

In 2018, I’d completed a six year, part-time creative writing degree and won the prize for best dissertation. I met wonderful people and was lucky enough for a tutor to become my mentor and editor. Thanks to this support, my poetic retelling of the Trojan war from the perspective of Thetis, mother to Achilles, was due to be performed in Scarborough this weekend. We’d begun the rehearsals when the world shifted into covid-hell, and the country divided along the lines of what was and wasn’t considered essential.

The preparations took me into a different place. Thesis time became Thetis time. I couldn’t summon the same interest which was driving my other work.

Instead of focusing the amendments, I wrote a new piece about Odysseus sailing home from Troy to Ithaca. It told of his time on the island of Ogyia with the goddess Kalypso. Whereas Thetis was written for the page, the Song of Kalypso emerged from hearing multiple voices speaking my lines. I began to understand how poetry changes when it’s listened to. It was case of practice emerging from theory. There were early talks around producing Kalypso for the stage later in the year but, like Thetis, the dates and details have become temporary unknowns.

I’m now researching 5th century Britain. The Romans have left and the Saxons are invading. Many Britains, romanised and christianised on the surface, retain close links to their celtic-pagan past. During these fractured times, the songs and sagas tell of a warrior who rose up to fight against the Danes and Angles. A soldier who became a king. His name was Artur.

Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and the Welsh Mabinogion, all offer the bones of something which might or might not have happened. In that fragile, shifting space there’s opportunities for the imagination to take flight. The facts, bare as they are, can be built on through poetic narrative. This is what I love.

I’d stopped loving my research in the same way.

I’ve made a new life. Amongst other things, I’ve become a beekeeper and have picked up the guitar again. During this year I found myself walking away from the doctorate. The rationale for investment had gone. Today, there’s so little space. Something would have to be abandoned. The new pillars of my world are my allotment, beekeeping and writing; I don’t want to give any of them up to make room.

This is my first post since the viva, seven months ago. I’ve travelled a long way in a short time and am no longer the same person. If anything, I feel more like myself than I’ve ever done. Looking back at all the qualifications and accreditations, all the projects, funded and otherwise, collected over the years, I can see I always multi-tasked on multiple levels, never stopping or pausing for breath. My feet didn’t touch the floor. Now I’m grounded in things which belong to me.

Remove the structure of your life and the daily routine of work, take away the rationale for getting up and out of the house, cut the threads of your identity, and what’s left?

Change often forces you to start from zero. To reassess what you already have. To understand and learn to appreciate what really matters.

It was tough but I’ve survived. Will I regret walking away from the PhD? I don’t think so because I’m learning there’s more important things.

It’s taken a long time to make the final decision. I thought about it for months, dithered for weeks, listened to what everyone had to say. In the end it came down to a phrase I saw in a motorway service station which seemed to speak directly to me.

‘You have one life – live it.’

For years I’ve complained about not having time to write. Now the time has been gifted and I’m going to make the most of it, for myself, doing what I’ve always wanted to do.

The Digital Academic has run its course.

All good things come to an end but – eventually – they can be replaced by things which feel even better…

Thank you to everyone who’s been with me on this journey, in particular over the past year. You know who you are and I’m truly grateful for all your support and kindness.

So, here it comes….