ALT and motherhood on the same page?

I didn’t see that coming!.

Last week Catherine Cronin and Frances Bell presented A personal, feminist and critical retrospective of Learning (and) Technology, 1994-2018 describing themselves as IT professionals, lecturers, community educators, postgraduate students, researchers, feminists, social activists, and mothers.

Since watching the live stream, I’ve been reflecting on political and critical perspectives and, following my last post Start the Week Backwards have written this response to the zeitgeist mood of the 25th ALTc.

My career’s been shaped by motherhood, divorcehood and resulting single-parenthood. Built round term-times, it was one long juggling act, never stopping, never resting, life full on until the nest was empty and I woke up one day with the whole weekend ahead and no idea of what to do.

It’s been liberating to acknowledge a gendered perspective to my decades working with education technology. Last week in Start the Week Backwards I returned to 1989, to my first degree as a mature ‘widening participation’ student, my early encounter with DOS computers running Wordstar and Lotus. I cried during an ‘IT Test’ when I accidentally pressed the Insert key. I didn’t know it existed, never mind why all my text was being overtyped.

I hope I never forget how that felt.

My first degree was transformative in so many ways. It cost me my marriage.

Apparently, no one likes a clever git.

I moved from country to inner city. It was February 1991. The coldest winter with the heaviest snow. My student loan fixed the boiler and bought a cooker. The second-hand electric shop wanted £5 for delivery. I borrowed a sack barrow and delivered it myself.

The greatest life lesson I learned was this.

Regardless of gender, the parent with the least earning potential takes on most of the childcare. A salutary lesson. A universal rule like Jane Austen on men and wives (note the primary identity!)

Before the start of the conversation started by Catherine and Frances, the last time I ‘outed’ myself as a parent was five years ago in Who will clean the toilets after the revolution This was my problem with feminism. The personal is political but it has to be practical too.

Today I’m comfortable in my empty nest and appreciate my freedom of choice. I admire colleagues who juggle full-time work alongside small children, especially those with babies. Feminism and equality campaigns have made flexible working possible, although I suspect it’s an ongoing struggle, financially, emotionally and physically. The women who make it are stars!

A personal and feminist lens shows gender affected me. Being a female of a certain age when I entered HE has influenced opportunities and choices. During Catherine and Frances’s presentation, I looked for a photo of myself with the children, realising for the first time how few there are. Lots of babies, with and without their father, but not with me. This was before the days of mobile phones and selfies – not that long ago – all I could find were two.

This is what happens to women in the home. They become invisible. It’s the public work versus the private ‘hearth and home’ binary all made real.

I wouldn’t have it any different, but I do sometimes wonder how different it might have been.

My career in adult, community and higher education has been eclectic, like so many others. An eclecticness shared so creatively in a timeline by Amber thomas, who gave a keynote at #ALTc. Throughout my working life, I’ve been a mother, step-mother, carer. Constant but rarely discussed. Why? Is it because I’ve worked mostly alongside men? I’ve never thought of this before. It shows the power of Catherine and Frances using the motherhood word in conjunction with technology, research, social activism. Been there. Done that. But it’s not often I’ve reclaimed gender in public.

Thank you women of ALTc, for giving us permission to do the same.

We need more stars!

Like so many women, I’ve done life backwards. Much of my knowledge is experiential. This means I often feel I’m swimming against the tide.

Practice can disempower in the way assumptions discriminate.

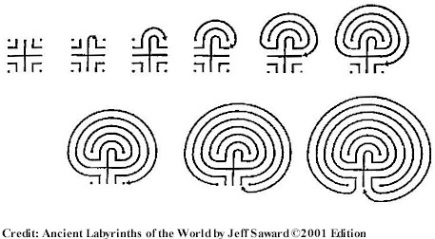

Being a female of a certain age, I feel othered in ways I imagine are not shared by men. I write about the digital but have analogue roots The ‘O’ word is banned. I refuse to accept life as linear. For me, it’s circular and spiral, like a a labyrinth. Remember the labyrinths? This is another area of work I’d love to resurrect, but people move on and the early momentum of a movement looking at walking meditative practice for learning development and reflection feels faded. At least the blog and the photos remain Walking the Labyrinth

Women who do too much!

Why are we so driven?

Age is discriminatory.

Socially, culturally, politically….

Take the phrase Early Career Researcher. It ‘Others’ me. I feel excluded. My PhD is the biggest independent piece of research I’ve done but in terms of time it’s late rather than early. I have two degrees and two Masters. I hold CMALT plus SFHEA. If I’m not an Early Career Researcher, what am I?

Identity has been an issue for some time.

I was Senior Lecturer in Education Development. Now I’m a Teaching Enhancement Advisor in Professional Services.

Take the word ‘academic’ off your employment contract and what does it mean?

Who am I within university tradition and practice? Where do I fit?

Amber’s keynote was inspirational. It spoke to all women with eclectic careers built round the public face of ed tech alongside the private space of hearth and home. Amber’s timeline reinforced how the industry continually transforms itself, creating new identities to solve the same old issues.

We know.

Our voices may have been silenced but we know what’s going on.

It’s not about the technology.

This is why the promised transformation hasn’t happened.

Like attracts like and technology determinist approaches won’t reach the non-digital whose doors are closed and habits fixed. This is not to belittle either but we need to talk. To everyone across borders and boundaries; to everyone involved in creating opportunities for students to learn.

We need to learn too.

I like an Appreciative Inquiry approach. This assumes the answers are in the room. Rather than investing in expensive external consultancy and the input of perceived ‘experts’, we should invest in exploring ways of sharing what we already know.

I like Jung’s theory of collective unconscious. I believe in the possibility of univerisal memories, that shared expereinces create energy. It explains the attraction of an open fire and the awe of layng on a hill top below a night sky full of stars.

Memories are strange phenomena. They disappear when you want them then reappear for no apparent reason. Proust’s Madeleine has happened to us all. Sarsaparilla on your tongue. Electric shivers from a full moon.

Pedagogic practice hasn’t really changed. My first experience of higher education was during A levels. I signed up for an evening class at the Universty of Hull. In the Wilberforce Building. Now I work there. The building has had a facelift but the rooms are fundamentally the same – small with no windows and rows of desks facing the front.

Last year I finished a part-time degree at Hull. Six years of attendance. Twelve modules taught in the same Wilberforce Building in rooms with rows of desks facing the front. No technology was used during the making of this degree. The only time the PC was switched on was student presentations where I used Powerpoint.

When is comes to teaching and leaning, technology is not the solution. There’s no magic tool to solve the problems but plenty of technology-based solutions which have added to them.

Learning and teaching is where we need to begin. The design of opportunities for learning with or without the tech. It’s 2018. It’s going to be in there somewhere, in the same way it’s at home and in the workplace.

So what are the problems?

Well, the status of being digitally literate for starters. This is a requirement which needs to be elevated alongside english and maths, but even so, technology is not the answer. Not on its own.

There are bigger issues.

Like widening participation; the opening up of university courses ‘… for all those who are qualified by ability and attainment to pursue them and who wish to do so.” (Robbins Report, 1963)

The NSS arrived with promises it would not lead to league tables when it was clear this was exactly what would happen. Today, the NSS combined with student fees, pose a potential (and predictable) perfect storm.

Despite it all, I still believe in the concept of higher education for the public good. The often quoted analogy of public good with lighthouses is – I think – apt. Shining light into darkness, warning of danger.

Danger?

Education can hurt and be uncomfortable. It should be full of liminal spaces and troublesome knowledge. Unfortunately, it can break relationships and create division – but also open hearts and minds, shine light on exclusion and discrimination, be a beacon for socially democratic thinking and provide opportunities for individuals to be transformed and thrive.

Why shouldnt it be for the public good?

Across the country, thousands are preparing for arrival on campus. Diverse cohorts are packing bags and preparing to leave home. Others are sitting late at night juggling the school run on paper with nursery pickups and contingency plans for when the grandparents are ill. Those who’ve had unexpected life changes are looking to university with no idea of what lies ahead. To those who are unsure, I’d say feel the fear and do it.

In all of this, the women working in higher education, in partcular in ed tech and digital practice, have their own unique contribution to make. Accustomed to suppressing the maternal and personal, they can add hugely to the collaborative processes of teaching and learning.

We need a platform and a voice.

I hope the conversations started at ALTc are enabled to continue.

images from ALT and pixabay

So here’s my top ten books choice from the research corner of my room.

So here’s my top ten books choice from the research corner of my room.